This post will explain, how to identify a function responsible for string deobfuscation in a native-PE malware sample. We will use a KpotStealer sample as a concrete example. KpotStealer (aka Khalesi or just Kpot) is a commodity malware family probably circulated in the shadowy parts of the internet since 2018. It got its name from a string publicly present on the Admin-Panel.

After we found the function we will understand the data structure it uses and emulate the decryption of a string with CyberChef and Binary Refinery. An interesting detail here is that Ghidra currently does not guess the function signature correctly.

Finally, we will develop a Java script (hehe) for Ghidra to automatically deobfuscate all strings given the corresponding obfuscation function.

## Motivation

Malware authors use string obfuscation to avoid inclusion of "interesting" strings as an entry point for bottom up analysis in the binary. Some time ago, I blagged about string obfuscation and how one might implement it. Feel free to head over there for more details and context.

The intention behind using string obfuscation is, to make assessments like "this looks like an IP, maybe it's the Command & Control (C2) server" or "

And this finally enables Ghidra to show us the following decompiled version of the function, which I also renamed:

vssadmin.exe Delete Shadows looks as if the malware deletes shadow copies" impossible. It would also hinder an analyst to find a reference to a POST string, which may indicate the place in the code where the networking is implemented. Obviously, an analyst wants to revert this process to be able to do exactly that. Especially if a malware family uses lots of strings or if one wants to analyze multiple samples of the same family, this process should be as automated as possible.

## Identifying the String Deobfuscation Function

Let's first assume that there is only one function responsible for deobfuscating all strings. This is true for the KpotStealer sample we will be looking at and so it is for many other malware families. Often, malware authors do not distinguish between strings requiring protection and generic strings and just apply string obfuscation to all strings in their code. This has two interesting implications for us as reverse engineers:

* since strings are generally quite important in software development, the string deobfuscation function is called from many different locations and probably also not far from the entry point of the executable.

* all locations, the string deobfuscation function is called from, belong to malware code and are not part of any static library. And we want to avoid reverse engineering static library code as a vampire wants to avoid garlic.

The first of the two points above suggest that starting off from the entry point top-down-style and systematically going through all functions may be feasible. To further speed up the process, I use the following heuristics:

* Since strings are so common, the string deobfuscation function should be called from a lot of different places.

* The string deobfuscation function should access at least one memory region (containing the obfuscated string). This region may be represented by a global pointer reference from within the function or be passed to the function as an argument. If the first of the two is true, the string obfuscation method needs some sort of id to distinguish different strings within that global buffer.

* Similarly, the function further needs access to a second buffer if it leverages cryptography to deobfuscate the string. This _key_ may be the same for all strings or may also vary on a per-string basis. If the second is true, the function may either receive different strings every time it is called or, again, some sort of id to distinguish different strings.

* The function needs some way to know, how large the obfuscated buffer is. Common ways of doing this in C are to use a terminating character (like \0) or a parameter explicitly stating the length.

* Deobfuscated data needs to be returned from the function. An obvious way would be to return a newly allocated buffer. Another way is, to write to a pointer passed as an argument to the function.

* At the call locations the deobfuscated data (somehow) returned from the function is often then used shortly after.

The whole point of all these heuristics is to be fast. Deobfuscating all strings normally is a huge step forward in the analysis of a malware and gives a jump start by enabling bottom-up analysis. On a different note, it sometimes even allows extraction of indicators of compromise (IoC) like IPs or domains, if that's your heart's desire.

## Finding Nemo

This and the following section will describe how one would find the function responsible for string deobfuscation in the KpotStealer sample with a SHA256 hash of

67f8302a2fd28d15f62d6d20d748bfe350334e5353cbdef112bd1f8231b5599d

0x004058fb sticks out because it is quite large and because it is setting a lot of global variables. It was only then, that I checked the number of import of the binary and realized that there are almost none. This may mean that this sample uses some sort of dynamic API resolution and the function at 0x004058fb is a prime candidate for being responsible of doing that: it is called relatively early during execution and sets a lot of global variables. Hence it is plausible (though not necessary), that it needs to reference strings containing DLL names.

Starting at 0x00405912, the function at 0x0040c8f5 is called multiple times. This function is also called at 69 other spots in the binary, which is a good tell that this may be the string deobfuscation method (you can see this by pressing X if you have the ghIDA key bindings for Ghidra configured). The weird thing is though, that Ghidra only shows

FUN_0040c8f5();

FUN_0040c8f5();

FUN_0040c8f5();

FUN_0040c8f5();

FUN_0040c8f5();

FUN_0040c8f5();

...

CALL, MOV and, LEA.

Let's first understand what these instructions to in general: CALL branches off execution to a function. This is done by pushing the address immediately after the CALL instruction onto the stack and then set EIP to the address of the function to be called - but we don't need to care about this level of detail here. The other one and a half assembly instructions MOV and LEA have different intended use-cases. But in principle, they both just move data around: LEA copies the _referenced_ data and MOV the actual data. But this difference does not matter if you just ignore [ and ] characters.

Let's move away from the general description to the concrete usage of these instructions here. When clicking on one of the functions in the decompile view, the disassembly listing will also move to the corresponding position in memory:

00405907 8d bd 78 f9 ff ff LEA EDI=>local_68c,[EBP + 0xfffff978]

0040590d b8 a6 00 00 00 MOV EAX,0xa6

00405912 e8 de 6f 00 00 CALL FUN_0040c8f5

00405917 8d bd 84 f9 ff ff LEA EDI=>local_680,[EBP + 0xfffff984]

0040591d b8 a7 00 00 00 MOV EAX,0xa7

00405922 e8 ce 6f 00 00 CALL FUN_0040c8f5

00405927 8d bd cc f9 ff ff LEA EDI=>local_638,[EBP + 0xfffff9cc]

0040592d b8 a8 00 00 00 MOV EAX,0xa8

00405932 e8 be 6f 00 00 CALL FUN_0040c8f5

00405937 8d bd e4 f9 ff ff LEA EDI=>local_620,[EBP + 0xfffff9e4]

0040593d b8 a9 00 00 00 MOV EAX,0xa9

00405942 e8 ae 6f 00 00 CALL FUN_0040c8f5

00405947 8d bd 9c f9 ff ff LEA EDI=>local_668,[EBP + 0xfffff99c]

0040594d b8 aa 00 00 00 MOV EAX,0xaa

00405952 e8 9e 6f 00 00 CALL FUN_0040c8f5

00405957 8d bd 58 f9 ff ff LEA EDI=>local_6ac,[EBP + 0xfffff958]

0040595d b8 ab 00 00 00 MOV EAX,0xab

00405962 e8 8e 6f 00 00 CALL FUN_0040c8f5

CALL is preceded by a LEA and MOV. All LEA instructions above move an address into the EDI register and the MOVs copy an immediate value into EAX. Before giving it any further thought, let's tell Ghidra to take EAX and EDI into account when generating decompiled code for these calls. Edit the function signature to "Use Custom Storage" and add two "Function Variables" stored in EAX and EDI. This leads to the following decompiled code:

FUN_0040c8f5(0xa6,local_68c);

FUN_0040c8f5(0xa7,local_680);

FUN_0040c8f5(0xa8,local_638);

FUN_0040c8f5(0xa9,local_620);

FUN_0040c8f5(0xaa,local_668);

FUN_0040c8f5(0xab,local_6ac);

uint PrStringIndex and BYTE *RetVal:

void FUN_0040c8f5(uint PrStringIndex, BYTE *RetVal)

{

int iVar1;

uint uVar2;

ushort uVar3;

iVar1 = (PrStringIndex & 0xffff) * 8;

uVar3 = 0;

if (*(short *)(&DAT_0040128a + iVar1) != 0) {

do {

uVar2 = (uint)uVar3;

uVar3 = uVar3 + 1;

RetVal[uVar2] =

(&PTR_DAT_0040128c)[(PrStringIndex & 0xffff) * 2][uVar2] ^ (&DAT_00401288)[iVar1];

} while (uVar3 < *(ushort *)(&DAT_0040128a + iVar1));

}

RetVal[*(ushort *)(&DAT_0040128a + iVar1)] = '\0';

return;

}

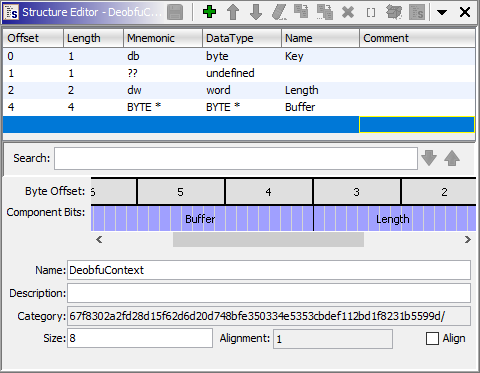

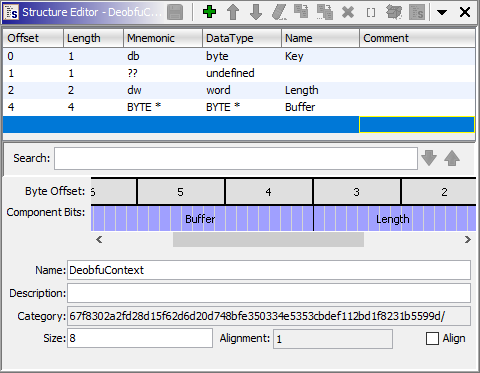

DAT_0040128a, PTR_DAT_0040128c and DAT_00401288. Just by looking at the auto-generate names, one can tell that the distance in memory between those three is very small (i.e. 2 bytes). This is a sign that those are not actually three different variables but a structure with three fields. And we also already know the sizes of two of them (and just assume 4 bytes for the last, mainly because that's the size of a pointer in 32 bit):

struct DeobfuContext {

word field_0; // because 0x0040128a - 0x00401288 == 2

word field_1; // because 0x0040128c - 0x0040128a == 2

dword field_2; // because this is the size of a pointer in 32-bit

}

DeobfuContext and don't forget to hit that other "Save" button in the "Structure Editor".

Now let's retype the variable that comes first in memory to a DeobfuContext struct. Double clicking DAT_00401288 will move the Listing view to the corresponding memory location. Since our structure is 8 bytes in size, we first need to make some space by undefining PTR_DAT_0040128c below (hit U if you - you might have guessed - have the ghIDA key bindings) and change the type of DAT_00401288 to DeobfuContext. This will lead Ghidra to show typecasts like (&DAT_00401288)[PrStringIndex].field_1, which tells us again that we made a mistake: The type is not DeobfuContext but an array of DeobfuContext. Since we don't know the size, we'll just use a size of 1 for now: Retype DAT_00401288 to DeobfuContext[1] and also rename it to DEOBFU_CONTEXTS. I also took the liberty to rename two local variables to i and j because they where used as counters in a loop:

void FUN_0040c8f5(uint PrStringIndex, BYTE *RetVal)

{

uint j;

ushort i;

PrStringIndex = PrStringIndex & 0xffff;

i = 0;

if (DEOBFU_CONTEXTS[PrStringIndex].field_1 != 0) {

do {

j = (uint)i;

i = i + 1;

RetVal[j] = *(byte *)(DEOBFU_CONTEXTS[PrStringIndex].field_2 + j) ^

*(byte *)&DEOBFU_CONTEXTS[PrStringIndex].field_0;

} while (i < DEOBFU_CONTEXTS[PrStringIndex].field_1);

}

RetVal[DEOBFU_CONTEXTS[PrStringIndex].field_1] = '\0';

return;

}

DeobfuContext struct: Because i counts up until field_1, it is probably some sort of length.

The expression *(byte *)(DEOBFU_CONTEXTS[PrStringIndex].field_2 + j) suggests, that field_2 is in fact an array, i.e. BYTE *, which - coincidentally - is also four bytes in size. And finally, *(byte *)&DEOBFU_CONTEXTS[PrStringIndex].field_0 effectively shortens the field field_0 to a size of one byte instead of two. One might also realized that this field_0 is used in an XOR expression ^ so let's be brave and guess that it's a key and change the struct accordingly:

And this finally enables Ghidra to show us the following decompiled version of the function, which I also renamed:

void EvStringDeobfuscate(uint PrStringIndex, BYTE *RetVal)

{

uint j;

ushort i;

PrStringIndex = PrStringIndex & 0xffff;

i = 0;

if (DEOBFU_CONTEXTS[PrStringIndex].Length != 0) {

do {

j = (uint)i;

i = i + 1;

RetVal[j] = DEOBFU_CONTEXTS[PrStringIndex].Buffer[j] ^ DEOBFU_CONTEXTS[PrStringIndex].Key;

} while (i < DEOBFU_CONTEXTS[PrStringIndex].Length);

}

RetVal[DEOBFU_CONTEXTS[PrStringIndex].Length] = '\0';

return;

}

DeobfuContext[183].

But before we move on and write code to automate this, just to eventually realize that we made a mistake somewhere above, let's first confirm our understanding of the deobfuscation algorithm by emulating it. There are numerous ways of doing that and I'll just explain, how to do it in Cyberchef and then, how to do it in Binary Refinery. Binary Refinery is the best set of command line tools for binary transformation out there. You can also always write a Python script or try to compile the code with a C compiler.

Let's take the first call that comes along (at 0x00405912): EvStringDeobfuscate(0xa6, local_68c). It will access position 0xa6 (which is 166) of the global array. Double click DEOBFU_CONTEXTS and scroll down to position 166:

| Field | Value

|--- |---

| Key | B4

| Length | 0B 00

| Buffer | 5c 2a 40 00

Double clicking the global variable DAT_00402a5c, which corresponds to the Buffer pointer 5c 2a 40 00, will bring you to the memory location containing the obfuscated string. We know, that it should have the size 0x0b (which is 11). Create an Array of that size in memory there, select it and, finally "Copy Special..." (or Shift-E) it. When choosing "Byte String (No Spaces)" the following data will be in your clipboard: c3dddadddad1c09ad0d8d8.

Using CyberChef for example, you can deobfuscate this with the "From Hex" and "Xor" operations to wininet.dll. Alternatively, the following Binary Refinery pipeline will yield the same result:

emit c3dddadddad1c09ad0d8d8| hex | xor H:B4

# alternatively, you can also read the string directly from the sample:

emit 67f8302a2fd28d15f62d6d20d748bfe350334e5353cbdef112bd1f8231b5599d | peslice 0x00402a5c -t 11 | xor H:B4

findGlobalBufferAddress function, which I'll explain in a moment. If that's not successful, it will ask the user for the address instead. To be honest, there is not much to see here:

long globalBufferPtr;

OptionalLong optionalGlobalBufferPtr = findGlobalBufferAddress(deobfuscator, 0x10);

if (optionalGlobalBufferPtr.isEmpty()) {

try {

globalBufferPtr = askInt("Enter Global Buffer Address",

"Cannot automatically determine global buffer address, specify it manually:");

} catch (CancelledException X) {

return;

}

} else {

globalBufferPtr = optionalGlobalBufferPtr.getAsLong();

}

findGlobalBufferAddress function, which is an example for parsing some assembly in a Ghidra script:

public Boolean isGlobalBufferAccess(Instruction instruction) {

return (instruction.getOperandType(0) & OperandType.REGISTER) == OperandType.REGISTER

&& (instruction.getOperandType(1) & OperandType.ADDRESS) == OperandType.ADDRESS

&& (instruction.getOperandType(1) & OperandType.DYNAMIC) == OperandType.DYNAMIC;

}

public OptionalLong findGlobalBufferAddress(Function func, int searchDepth) {

int i = 0;

for (Instruction instruction : currentProgram.getListing().getInstructions(func.getEntryPoint(), true)) {

if (instruction.getMnemonicString().equals("LEA")) {

// the first operand of LEA is the target register, the second is the address

if (isGlobalBufferAccess(instruction)) {

// this gets the "objects" for the second argument which. This is an array of

// values:

//

// LEA globalBufferIndex,[globalBufferIndex*0x8 + GLOBAL_BUFFER]

// Index 0: globalBufferIndex

// Index 1: 0x8

// Index 2: GLOBAL_BUFFER

String hexEncoded = instruction.getOpObjects(1)[2].toString();

return OptionalLong.of(Long.decode(hexEncoded));

}

}

i++;

if (i > searchDepth)

break;

}

return OptionalLong.empty();

}

LEA instructions. We guess that it is in fact the instruction accessing the global buffer if its first operand is a register and the second a calculated address. For an assembly instruction object, Ghidra exposes the "operand objects" which represent the values of the different operands of an argument to an instruction. The second argument to this LEA instruction is [globalBufferIndex*0x8 + GLOBAL_BUFFER] and there, we are interested in the third operand, the GLOBAL_BUFFER. Feel free to read the comment in the function for a slightly different perspective.

Step 5: The actual decryption of the string _should_ of course be the interesting part but as it's always, everything else already took 80% of the time. But still, here we go:

byte structContent[] = getOriginalBytes(toAddr(globalBufferPtr + globalBufferIndex * 8), 8);

byte xorKey[] = { structContent[0] };

int dataLength = (structContent[2] & 0xff) | (structContent[3] & 0xff) << 8;

int encryptedPtr = (structContent[4] & 0xff) | ((structContent[5] & 0xff) << 8)

| ((structContent[6] & 0xff) << 16) | ((structContent[7] & 0xff) << 24);

byte[] obfuscatedBuffer = getOriginalBytes(toAddr(encryptedPtr), dataLength);

byte decrypted[] = deobfuscateString(obfuscatedBuffer, xorKey);

getOriginalBytes from previous blag posts and reads 8 bytes of memory from the correct location. The first byte is the xorKey. Bytes at location 2 and 3 are combined little endian-style into an integer dataLength and finally, the four following bytes are combined in the same way into a pointer to the encrypted payload encryptedPtr. We then use the getOriginalBytes function again to read the encrypted data into obfuscatedBuffer and pass that together with the key to the deobfuscateString function:

private byte[] deobfuscateString(byte[] data, byte[] key) {

final byte[] ret = new byte[data.length];

for (int k = 0; k < data.length; k++)

ret[k] = (byte) (data[k] ^ key[k % key.length]);

return ret;

}

CALL Address | Offset | Deobfuscated String

|--- |--- |---

| 0x0040F6FE | 0 | http[:]//bendes.co[.]uk

| 0x0040F709 | 1 | /lmpUNlwDfoybeulu

| 0x0040FC5D | 2 | 4p81GSwBwRrAhCYK

| 0x00411D79 | 3 | SQLite format 3

| 0x00412C84 | 4 | 2|NordVPN||%s|%s

| 0x0040F714 | 19 | .bit

| 0x00412A85 | 20 | %08lX%04lX%lu

| 0x0040BB31 | 22 | Hostname

| 0x00409FC0 | 25 | TRUE

| 0x00409FCB | 26 | FALSE

| 0x00410134 | 27 | quit

| 0x0040DF67 | 45 | Software

| 0x0040DF72 | 46 | Microsoft

| 0x00412603 | 63 | pstorec.dll

| 0x0041260E | 86 | Internet Explorer

| 0x00409FB5 | 89 | %s TRUE %s %s %d %s %s

| 0x0040BB25 | 96 | logins

| 0x0040BB3D | 97 | encryptedUsername

| 0x0040BB49 | 98 | encryptedPassword

| 0x0040C5CF | 89 | %s TRUE %s %s %d %s %s

| 0x0040F83F | 119 | dotbit.me

| 0x0040F5DF | 122 | %S %s HTTP/1.1 %SContent-Length: %d

| 0x0040FF36 | 140 | %FULLDISK%

| 0x0040FF43 | 141 | %NETWORK%

| 0x00410CCE | 143 | %02d-%02d-%02d %d:%02d:%02d

| 0x00410A5E | 144 | MachineGuid: %S

| 0x00410ADD | 145 | IP: %s

| 0x00410B0A | 146 | CPU: %s (%d cores)

| 0x00410B91 | 147 | RAM: %s MB

| 0x00410C03 | 148 | Screen: %dx%d

| 0x00410CDB | 150 | LT: %s (UTC+%d:%d)

| 0x00410D57 | 151 | GPU:

| 0x00410E0A | 152 | Layouts:

| 0x00410E72 | 153 | Software:

| 0x004096EA | 154 | PWD

| 0x00409704 | 155 | CRED_DATA

| 0x00409711 | 156 | CREDIT_CARD

| 0x0040971E | 157 | AUTOFILL_DATA

| 0x004096F7 | 158 | IMPAUTOFILL_DATA

| 0x00410928 | 159 | SYSINFORMATION

| 0x004097F3 | 160 | FFFILEE

| 0x0040FF1C | 161 | __DELIMM__

| 0x0040FF29 | 162 | __GRABBER__

| 0x00405912 | 166 | wininet.dll

| 0x00405922 | 167 | winhttp.dll

| 0x00405932 | 168 | ws2_32.dll

| 0x00405942 | 169 | user32.dll

| 0x00405952 | 170 | shell32.dll

| 0x00405962 | 171 | advapi32.dll

| 0x00405972 | 172 | dnsapi.dll

| 0x00405982 | 173 | netapi32.dll

| 0x00405992 | 174 | gdi32.dll

| 0x004059A2 | 175 | gdiplus.dll

| 0x004059B2 | 176 | oleaut32.dll

| 0x004059C2 | 177 | ole32.dll

| 0x004059D2 | 178 | shlwapi.dll

| 0x004059E2 | 179 | userenv.dll

| 0x004059F2 | 180 | urlmon.dll

| 0x00405A02 | 181 | crypt32.dll

| 0x00405A12 | 182 | mpr.dll

## Conclusion

In my experience, scripting in Ghidra is much easier when done with Java. Even though you might not like the language, the documentation and eclipse integration is awesome which really speeds up the process. Apart from previously published snippets this post also covers parsing of assembly instructions.

The KputStealer family yields yet another good example for string obfuscation and a good exercise on how to find and reverse engineer it. This particular case also shows a situation where the decompiled failed and needs some help from the analyst.

2 Replies to “Use Ghidra to decrypt strings of KpotStealer malware”